COLLECTABLE STORIES: SLAVIC COWBOY

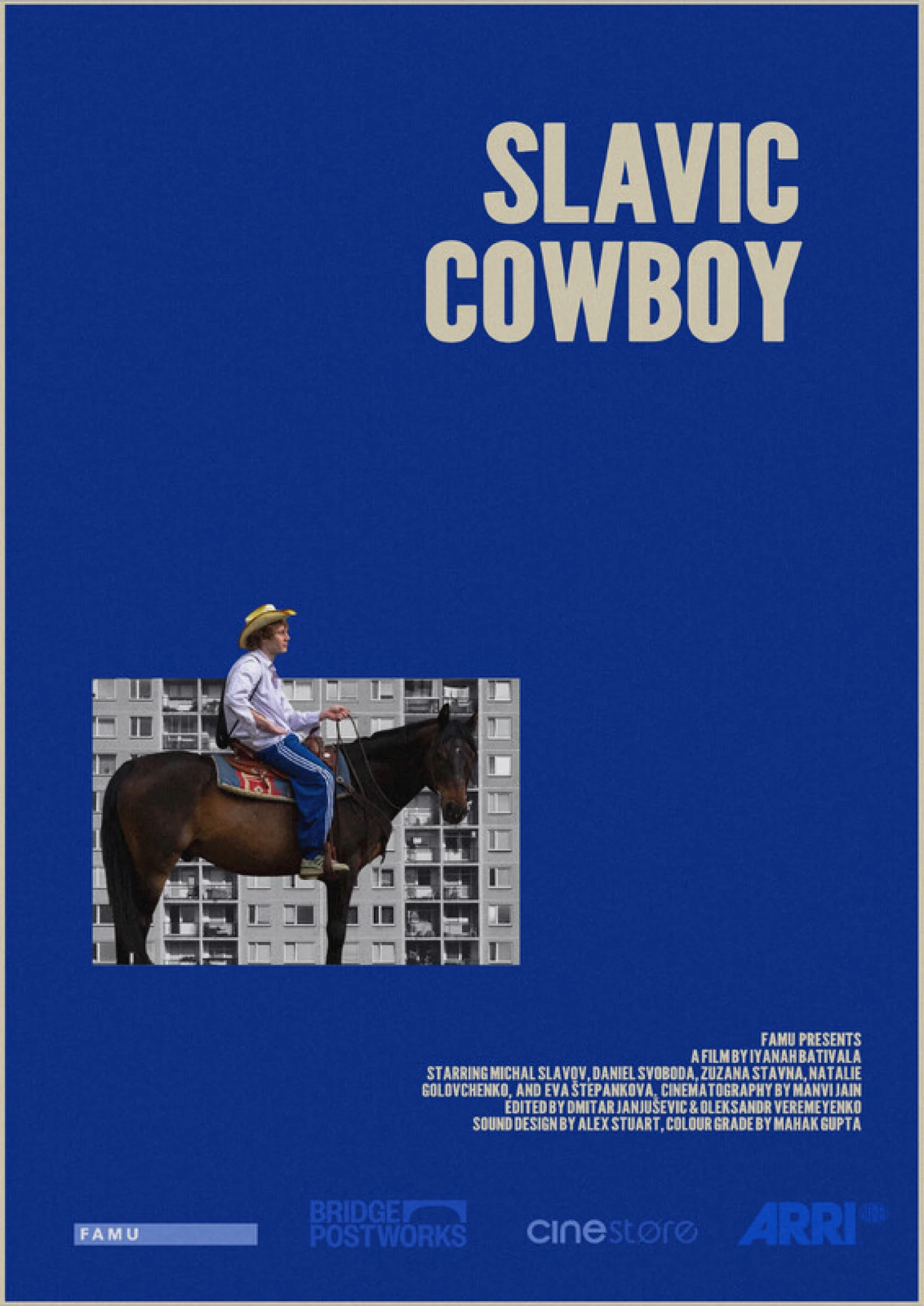

SLAVIC COWBOY

Short Talk with Iyanah Firdaus Bativala (Director) and Oleksandr Veremeyenko (editor)

BEST SHORT STUDENT FICTION FILM Category

22nd IN THE PALACE International Short Film Festival 2025

Czech Republic, Fiction, Czech, 00:17:46, 2024

Synopsis: KUBA, a socially stunted young man, lives his life through the fantasies he tries to sell to himself and the people around him. In his head he's been a football coach, a lion tamer, and now his latest pipe dream - a cowboy. He attempts to bring his dream to fruition by joining a niche Rodeo community in the Czech Republic, living out an outdated notion of the American dream in the heart of Central Europe.

Biography: Iyanah Bativala, born in New York and raised in Mumbai, began her film studies at Cornell University and is currently pursuing an MFA in Directing at FAMU (The Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague). With three years of professional screenwriting experience, she has contributed to several projects, including working in the writers' room for the upcoming Amazon series, Waack Girls, set for release in November 2024.

Iyanah Firdaus Bativala, director

Iyanah Firdaus Bativala, director

Toma Manov: Slavic Cowboy, that’s a very interesting title. Is there something specific you’re trying to provoke in the audience with that title?

Iyanah Firdaus Bativala : Well, in Czech, it’s actually Panelák Cowboy. But I thought in English, the word panelák [tower block building] doesn’t really translate if you’re not from this part of the world. So more generally, Slavic Cowboy made sense in that context.

Toma Manov: Oleksandr, since there’s a very strong contrast in tone between the urban space and the space in nature, was there anything specific you did in the editing to help distinguish the two?

Oleksandr Veremeyenko: I think where you see the panelák, it’s a lot more rushed, he’s late for the job interview in the beginning, and I tried to sort of push that feeling. It was more about showing that he really cares about getting to the ranch. And of course, once he’s with the horses, the rhythm slows down. There are longer shots, it’s more peaceful, just a calmer pacing overall.

Toma Manov: And since we’re talking about the horses, normally, a horse can be interpreted as a symbol of freedom. Is that something you were going for in the film?

Bativala: Definitely, freedom, but I also think belonging is what my character is looking for the most. And that’s really what the film is about - finding a community, finding a place where you belong. So yes, while the horse and the open field evoke freedom, it’s also tied to his sense of longing for connection.

Toma Manov: He wants to belong to a different community than the one he’s physically in?

Bativala: Exactly. He doesn’t fully belong to either one and that’s really where his struggle is. He’s not at home in the panelák community, and also not fully part of the rodeo world either.

Toma Manov: And speaking of the horse since there are scenes involving the animal, was any special training necessary for the actor?

Bativala: So actually, we only had one trained film horse for the scene where the horse is in the panelák. But all the other horses were untrained, just the ones that were already at the ranch where we shot. What I learned from this film is that, when you’re shooting with an untrained horse, you need to have an emotional support horse behind the camera.

Toma Manov: How does that work?

Bativala: The support horse just stands there, off-camera. It helps keep the other horse calm. If it’s not there, the horse on screen can panic.

Toma Manov: And since I read in your bio that you were born in New York and then grew up in Mumbai, this film feels very different from that background. Did your personal aesthetic influence the film, or how did the idea come about?

Bativala: So I noticed this rodeo or Western subculture almost as soon as I got to the Czech Republic. Coming straight from the U.S., it was really fascinating to me, it grabbed my attention. And after spending years in Central Europe, I’ve also come to really love this post-Soviet aesthetic. I don’t know maybe it’s a bit of exoticizing the panelák.

Oleksandr, how did your collaboration come about?

Veremeyenko: I think it was great. There was a first editor, and then I came on later. What I decided to do was include dream sequences to try and really bring the director’s vision to life, this dream or longing the character has. And I think we achieved that.

Interviewer: Toma Manov

Editor: Martin Kudlac